If the current April to June Gu season rains fail, food prices continue to climb dramatically, and humanitarian assistance is not scaled up to reach the country’s most vulnerable residents, several places across Somalia are at risk of famine (IPC Phase 5) until June 2022. Hawd Pastoral of Central and Hiran, Addun Pastoral of Northeast and Central, Bay Bakool Low Potential Agriculture, and IDP settlements in Mogadishu, Baidoa, and Dhusamareb are among these locations.

Since the beginning of 2022, acute food insecurity in Somalia has gotten much worse, with an estimated 4.8 million individuals (or 31% of the entire population) already experiencing Crisis or worse (IPC Phase 3 or higher) outcomes. During the April to June 2022 projection period, more than 6 million people (or 38 percent of the total population) are predicted to face Crisis or worse (IPC Phase 3 or higher) outcomes, with 1.7 million peiople in Emergency (IPC Phase 4) and over 81,000 likely in Catastrophe (IPC Phase 5). Other areas of humanitarian concern include the livelihood zones of Southern Agropastoral, Southern Rain-fed Agropastoral of Middle and Lower Juba, and Togdheer Agropastoral, as well as IDP settlements in Burao, Garoowe, Belet Weyne, Doolow, and Kismaayo, which are all facing Emergency (IPC Phase 4) between April and June 2022.

The rapid increase in the size of the food insecure population, the influx of newly displaced people, widening of household food consumption gaps, loss of livelihood assets, and worsening acute malnutrition are quickly outpacing current levels of humanitarian food assistance, which reached 1.3 million people in January and 2 million people in February. Past trends show that multi-season droughts in Somalia can lead to famine, as seen in 2010-2011 when an estimated 260,000 people perished from hunger-related causes. During the severe drought of 2016-2017, timely humanitarian response saved more disastrous outcomes. Between now and June 2022, urgent and prompt scaling up of humanitarian aid is essential to avoid extreme food security and nutrition outcomes, including the possibility of famine. Furthermore, through late 2022, humanitarian needs are likely to remain significant.

The intensifying multi-season drought that has gripped Somalia since late 2020 is to blame for the country’s poor food security and nutrition status in several sections of the country. Insecurity, violence, and unresolved political tensions – particularly in central and southern Somalia – are compounding the food security situation, as are global supply and price shocks. The consequences are numerous, including severe water scarcity, an increase in livestock deaths due to starvation and disease, a string of poor or failed harvests, escalating local and imported food prices, and drought and conflict-induced population displacement, all of which are reducing the poor and vulnerable population’s coping capacity.

After the inadequate Deyr rains in late 2021, the dry and hard Jillaal season of January to March 2022 exacerbated the severity of drought conditions. Water shortages, reduced milk availability, and a scarcity of saleable animals are currently affecting households, as animals die of malnutrition and the bodily condition of remaining livestock deteriorates. Pastoral households are heavily in debt due to increased prices of water and feed for cattle, as well as migration to remote places in quest of pasture and water. Low water levels in the Juba and Shabelle Rivers have severely disrupted cash crop and off-season grain production in riverine areas, causing further disruption to agro-pastoral and riverine livelihood zones. Poor harvests have also had a negative impact on poor households who rely on income from agricultural jobs. Domestic grain shortages, reduced regional basic food supplies owing to drought in neighboring countries, and a record rise in global food prices have pushed staple food costs out of reach for most impoverished rural, urban, and displaced families who must buy the majority of their food.

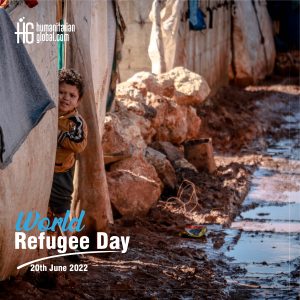

Food prices are projected to rise further in the coming months as a result of the crisis in Ukraine‘s influence on production and supply chains, putting millions of Somalis’ food security at risk. IDPs and the urban poor are also affected by rising food prices since they already spend a disproportionately significant share of their income on food (60-80%), have few chances to improve their incomes, and have a very limited capacity to absorb the impact of future rises in food prices. As a result, many rural households are seeing their food consumption gaps expand, and their ability to cope is being hampered by the destruction of their livelihoods. In many sections of the country, social support services are becoming increasingly overburdened. As a result of these circumstances, a boom in population displacement from rural areas to IDP settlements, towns, and cities has occurred. According to UNHCR data, up to 646,000 people have been displaced as a result of the drought since October 2021.

In many areas of central and southern Somalia, acute malnutrition is already at critical levels, and the number of severely malnourished children admitted to treatment centers is fast increasing, with two to four-fold increases reported in several districts. Acute watery diarrhea (AWD) outbreaks have been reported in several sections of the country as food security situations deteriorate and water availability and quality deteriorate. Disease incidence is leading to rising levels of acute malnutrition, as seen by the increasing number of moderately and severely malnourished children referred to treatment centers, which is accompanied by an increase in measles cases.

Pastoralists have been compelled to travel to remote grazing areas due to water and pasture limitations in pastoral communities. Poor pastoralists in many locations are unable to cope with growing water and food prices, particularly when they are already seeing a considerable drop in saleable animals due to distressed sales, weak/emaciated body states, and excess mortality. Poor pastoral households would have moderate to significant food consumption gaps through June 2022, with fewer livestock births projected, reduced revenue from livestock sales, and a low supply of milk for both adults and children. As a result, most pastoral livelihoods in Somalia are categorized as Crisis (IPC Phase 3) between April and June 2022, with Hawd Pastoral of the Northwest, Northeast, and Central, and Addun Pastoral of the Northeast and Central, respectively, classified as Emergency (IPC Phase 4).

A majority of the estimated 2.9 million IDPs in Somalia are poor, with few livelihood assets, few income-earning options, rising food prices, little access to communal support, and a significant reliance on external humanitarian assistance. Since late 2021, population displacement has escalated dramatically due to persistent drought and warfare. As a result, the number of IDPs in existing settlements is growing, and new IDP settlements are springing up in the worst-affected areas, with new IDPs coming in desperate circumstances and sometimes encountering multiple hurdles in obtaining humanitarian assistance once they arrive. Increased population displacement from rural to urban areas and IDP settlements is probable through mid-2022, especially if humanitarian assistance is not immediately scaled up and able to reach the most impacted areas, due to expected increasing drought conditions and prolonged insecurity. As a result, by mid-2022, a considerable number of IDPs will endure moderate to large food consumption gaps. Between April and June 2022, the majority of Somalia’s major IDP camps will be designated as Emergency (IPC Phase 4). Burco, Lasaanod, Garowe, Galkacyo, Dhusamareb, Beletweyne, Mogadishu, Baidoa, Dollow, Dhobley, and Kismayo are among the IDP settlements.

Since 2021, rising food prices have posed a major threat to food security in most Somali cities, particularly among the urban poor, who already spend a disproportionately large portion of their income on food (60-80 percent), with little room to absorb the impact of further increases in food prices and few opportunities to expand their incomes. As a result of falling labor wages and rising food costs, the terms of trade between wage labor and cereals have fallen by as much as 50% in some circumstances. As a result, through mid-2022, the urban poor would confront moderate to substantial food consumption discrepancies. Between April and June 2022, the majority of Somalia’s metropolitan areas are classed as under crisis (IPC Phase 3). This includes Hargeisa, which recently experienced a large fire that destroyed the majority of the enterprises in the main market, which traditionally provided work and nutrition to the city’s destitute.